As global momentum builds toward carbon neutrality and the circular economy, Mazda is accelerating its resource circulation initiatives. Mazda has actively committed to recycling car parts since the 1990s, long before environmental issues became as prominent as they are today. In this article, we take a look at the behind-the-scenes story of the disposal phase in Life Cycle Assessment*.

2025.11.27

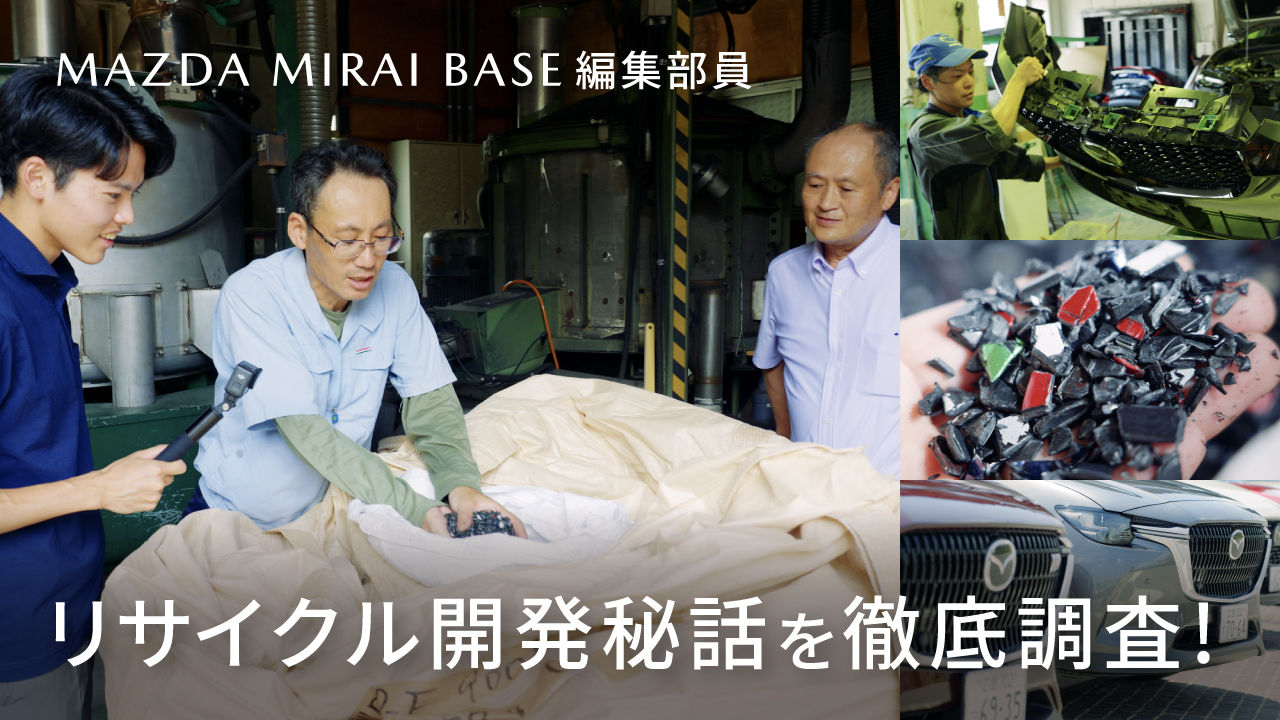

Mazda's Forward-Thinking Recycling: How Hiroshima Came Together to Overcome Technological Barriers - The Road to Carbon Neutrality Episode 5 -

* Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a method for evaluating environmental impact, such as CO2 emissions, throughout a product's lifecycle, from production and transportation, to use and disposal. Navigating Sustainable Management with LCA: Mazda's 2050 Carbon Neutrality Mission

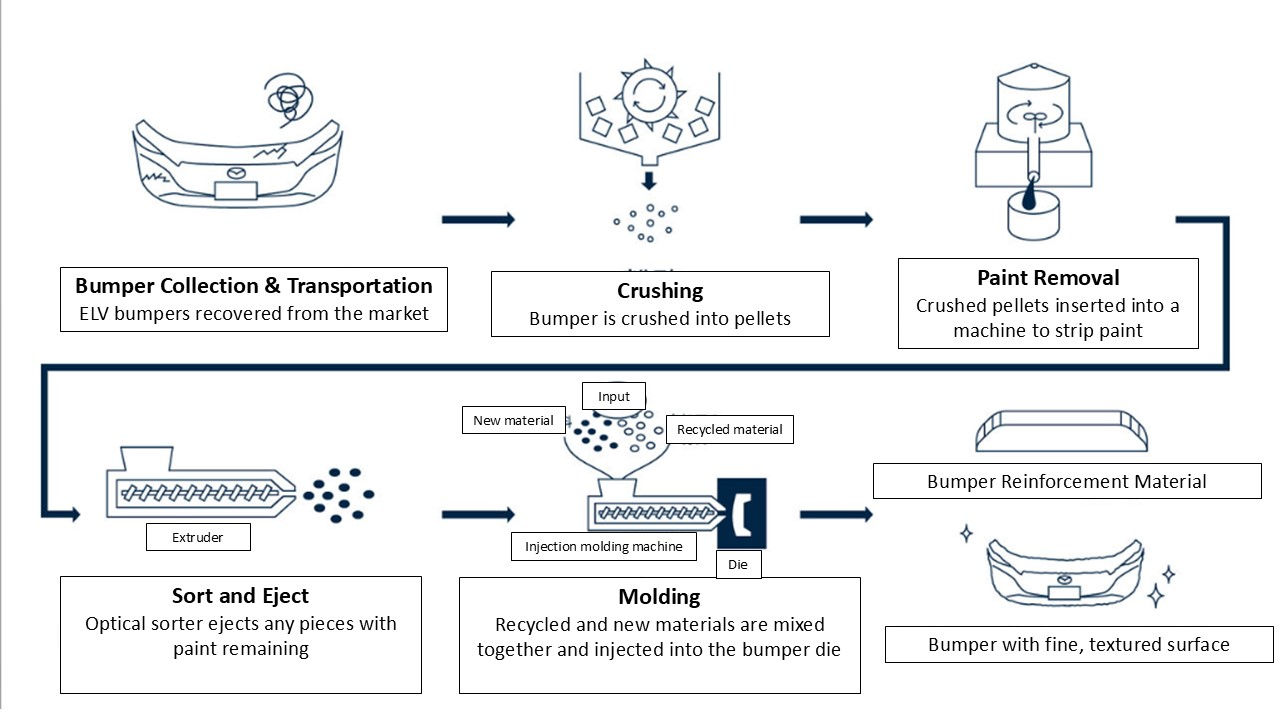

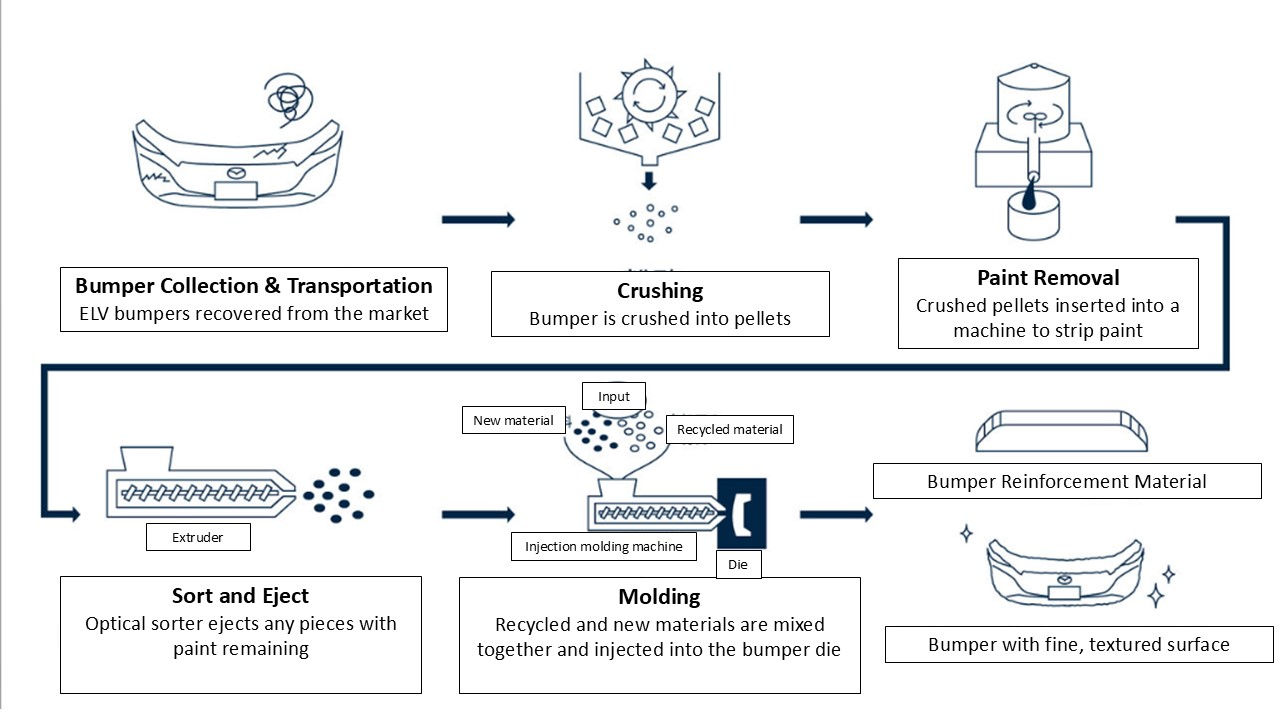

Mazda's recycling efforts are embodied in “Bumper to Bumper,” a technology that collects end-of-life vehicle bumpers (ELV bumpers), crushes and reuses the material to transform them into bumpers for new vehicles. While , many manufacturers abandoned this challenge due to its high technical hurdles, Mazda continued research and development from the 1990s. Through repeated trial and error with regional partners, in 2005 Mazda established a new business model covering everything from collection to recycling, creating approximately 1.27 million bumpers to date.

Kenta Usui, one of the newest members of the MAZDA MIRAI BASE team, investigates this development story and discovers what it takes to build a sustainable future.

Kenta Usui from MAZDA MIRAI BASE editorial team.

The Quest for Safe, High-Quality Recycled Materials

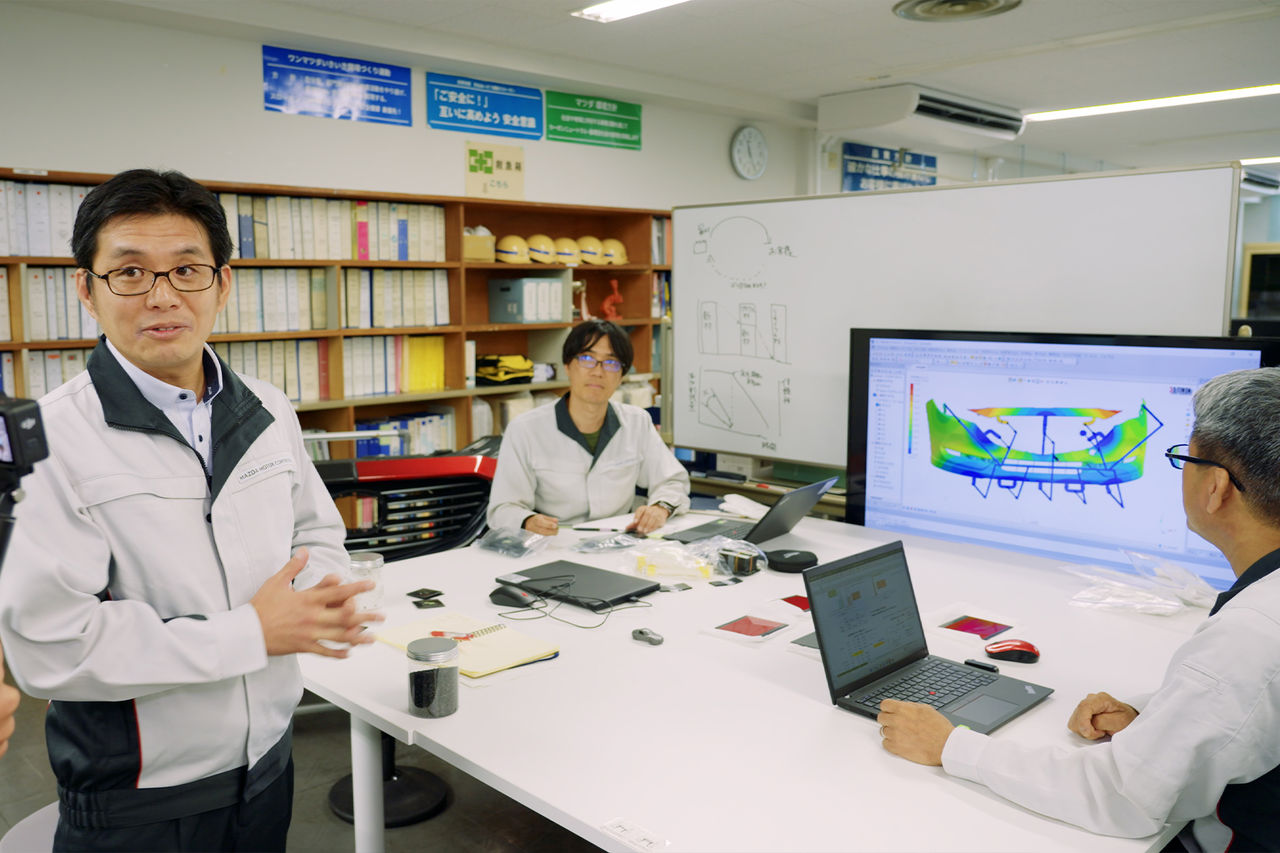

Have you ever wondered what happens at a car recycling site? To find out, Usui visited the Resource Circulation Project Team working on future recycling at Mazda. He spoke with Satoshi Furukawa, who leads research and development, to learn more about the recycling process.

Usui:

I understand that your focus is research and development in recycling, but what are you working on specifically?

Furukawa:

In recycling, plastics used in cars are crushed into fine pieces, melted, and returned to raw plastic resin that can be processed into parts. But these recycled materials have deteriorated from heat and UV exposure, and contain foreign substances like adhesives and paint, so they can't be used as-is.

Our role is to research and study how to increase the ratio of recycled materials that can actually be used.

Satoshi Furukawa of Mazda's Resource Circulation Project Team (left). Furukawa is a plastic materials specialist who conducted joint research with Hiroshima University on plastic degradation and regeneration mechanisms. He applies the technology and knowledge cultivated through industry-academia collaboration.

Usui:

How do recycled materials differ from new ones?

Furukawa:

Recycled materials contain minute foreign substances as bumpers on shipped cars are painted to match the body color. These create an unevenness on the surface when which isn’t present when using new materials. Another difference is in how the bumpers absorb impact. Those made only from recycled materials can't fully absorb impact energy, cracking easily.

That's why we mix recycled materials with new ones. We test different mixing ratios and evaluate whether they meet our standards for paint quality and vehicle performance.

Usui:

When I compare them by touch, recycled materials feel like they will crack easily, possibly because of the foreign substances. But the new plastic has rubber-like elasticity, which suggests better impact absorption.

When pressure is applied, new materials absorb the impact, but recycled materials crack if it contains foreign substances.

Furukawa:

Exactly. The foreign substances are the weak point. When the bumper takes an impact, it cracks at those spots. Removing foreign substances is the key.

The Technology Behind Mazda’s Pioneering Implementation of Bumper to Bumper

Usui:

When we think of cars, metal is a more obvious material. Is plastic really that common?

Furukawa:

More than you'd expect. Roughly half a car's volume is plastic - about 150kg per vehicle. The entire front end around the bumper is predominantly plastic. You'll find it around the driver's seat, the doors, and in areas you can't see, like the engine compartment.

Usui:

I had no idea. Does this bumper contain recycled material?

Furukawa:

Yes, about 5%. We collect roughly 40,000 ELV bumpers every year and give them new life on Mazda vehicles.

Usui:

That's a lot of bumpers!

Furukawa:

We've been doing this for over 30 years. Back in 2005, Mazda pioneered the technology to transform old bumpers into new ones: Bumper to Bumper. We're building on what our predecessors started.

Usui:

Thirty years. Did Mazda develop this project independently?

Furukawa:

No, we collaborated with multiple companies. Recycling bumpers back into bumpers seemed nearly impossible back then. The quality standards for bumpers are high, and we faced serious technical challenges. We needed partners with the right expertise. We found companies from completely different industries here in Hiroshima. Together, we worked through the obstacles.

Usui:

So it involved not just the car industry but partners from other fields. How did this all come together?

Breaking Through the 98.5% Paint Removal Rate Barrier

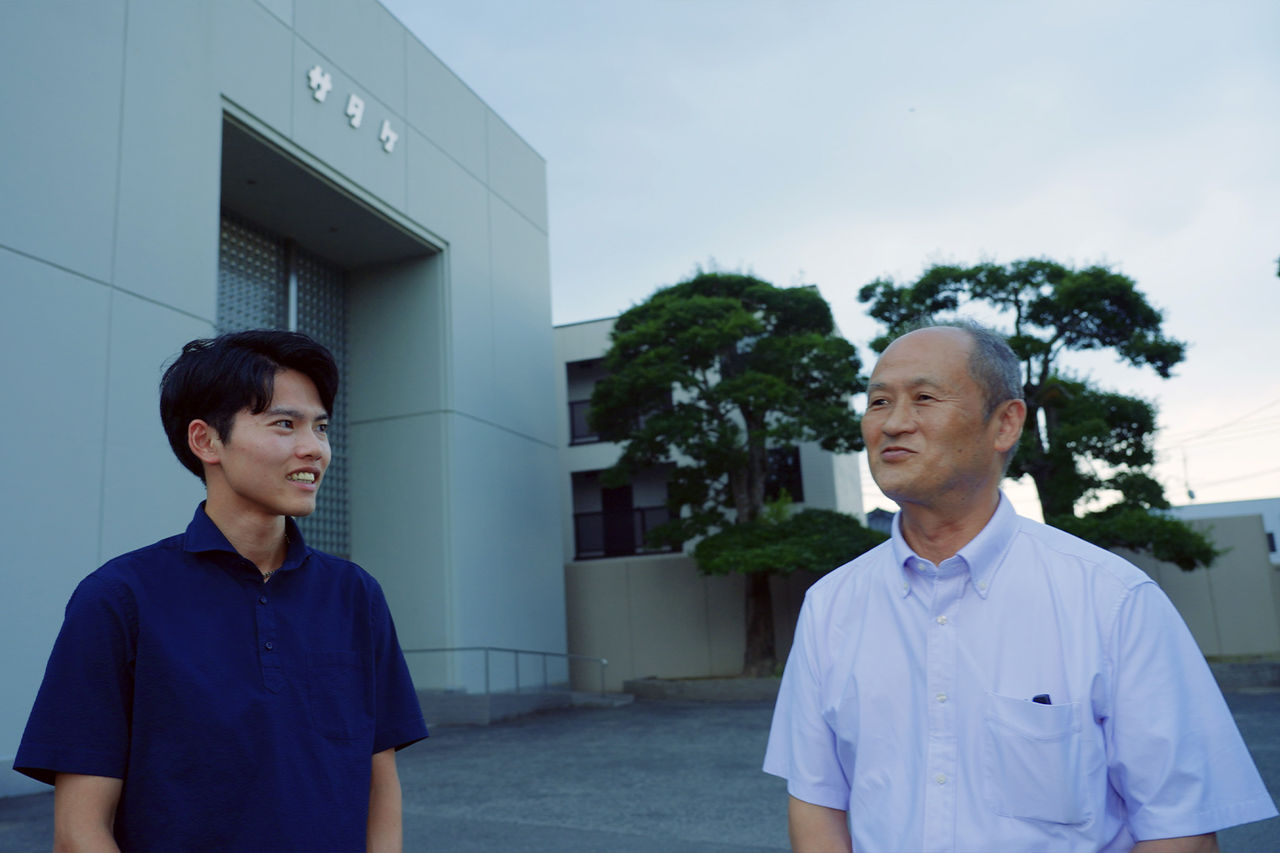

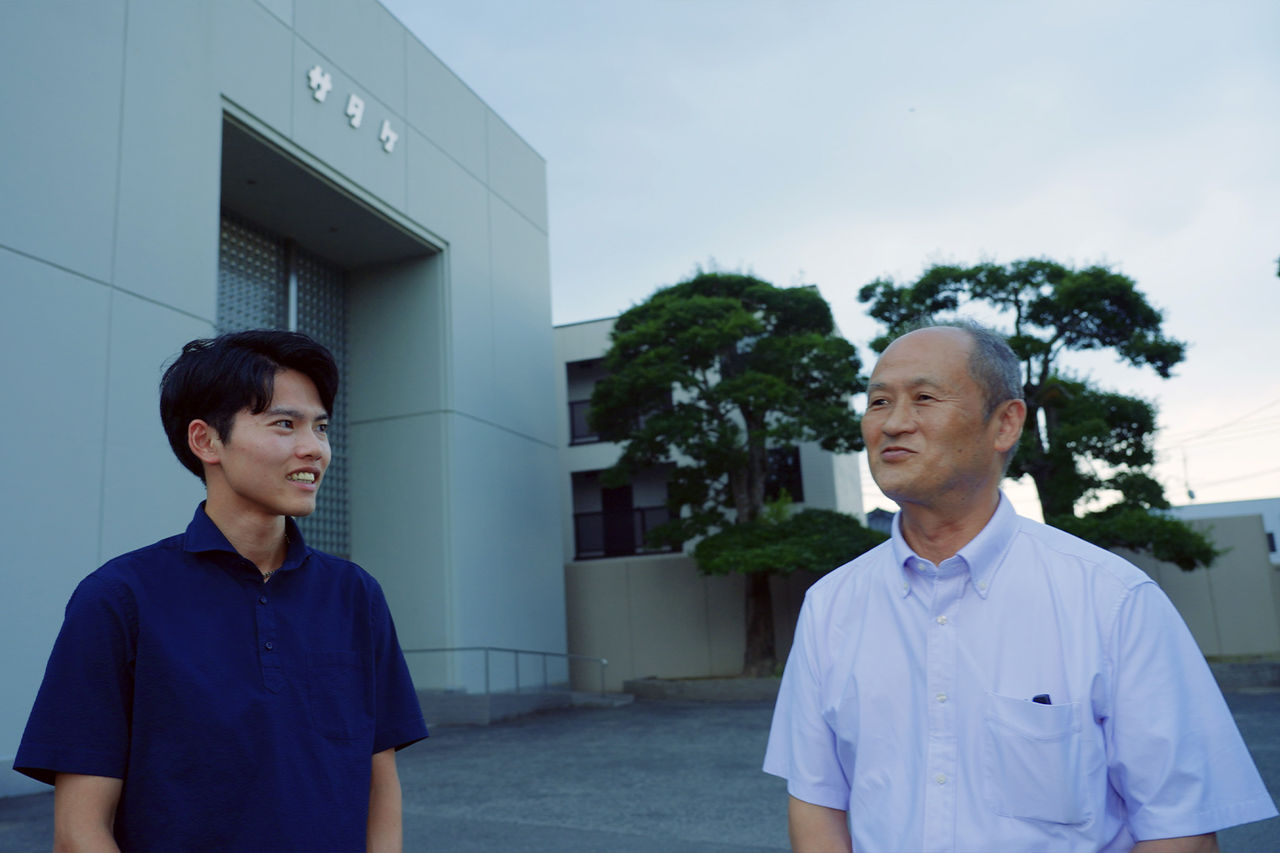

To understand how Bumper to Bumper came to be, Usui visited the people who made it happen. He toured former partner companies with Kenji Moriwaki, the Mazda engineer who led the development.

First stop: Takase Gosei Kagaku Corporation , which operates a factory that strips paint from collected bumpers and turns them into recycled materials. Tomomi Takase, the company CEO, worked alongside Moriwaki on the original development.

Usui:

I understand Mazda and Takase Gosei Kagaku jointly developed this technology. How did the project begin?

Moriwaki:

It all began in 1991. Mazda were concerned with how we disposed of bumpers. So we made a declaration ahead of other companies: burying or burning plastic harms the environment, and we were going to pursue material recycling instead. Bumpers are heavily plastic. If we could recycle them, we'd help the environment while making economic sense. That's where we started. That was the beginning of Bumper to Bumper.

But once we got going, we hit challenge after challenge. It was a long, hard road ahead.

Kenji Moriwaki, who worked on Mazda's Bumper to Bumper development 30 years ago.

Usui:

What was the biggest obstacle?

Moriwaki:

At first, we melted down bumpers with the paint still on, turned them back into resin pellets, and then molded new parts. But this weakened the material's tensile strength. Under impact, when forces pull and stretch the bumper, it would just snap.

And if even tiny traces of paint remain, you get surface defects on exterior parts. That ruled out using the material for bumpers, which require extremely high quality standards. Other manufacturers were attempting this too but everyone struggled with the same barriers.

Usui:

So the key was removing the paint completely.

Moriwaki:

Exactly. We focused on paint removal and started researching companies with that capability. We identified about 20 factories nationwide that produce recycled materials and evaluated their paint stripping technology. Takase Gosei Kagaku stood out. A company with proven paint removal capabilities was right here in Hiroshima. It felt like fate. I went to see them immediately.

Takase:

We had high-heat paint stripping technology developed by my predecessor. Back then, several car manufacturers came to us with similar requests, not just Mazda. What's remarkable is that 30 years later, Bumper to Bumper is still running strong.

Tomomi Takase of Takase Gosei Kagaku Corporation.

Usui:

Is it really that difficult to remove paint to the level needed for bumpers?

Takase:

Very difficult. Moriwaki's target was 98.5% paint removal. An extremely high standard. Honestly, it was a struggle to achieve.

Moriwaki:

The machine scrapes paint off the surface, but car parts have contours and recesses. Paint in those recessed areas is stubborn and difficult to remove. If you keep scraping to get it all, you reduce the material itself and lose yield. Removing paint from difficult to see areas without sacrificing yield - that was our major obstacle.

Takase:

We couldn't hit the target for quite some time. Even when we reached levels other companies would accept, Moriwaki would say, "The appearance quality still suffers. Can you get us another 0.5%?" Honestly, chasing that last 0.5% was really tough, not gonna lie!

Moriwaki:

Takase pushed hard for us and got us to that 98.5% threshold. But in actual factory production, you get variation and some pieces fell below 98.5%.

To consistently meet the target in production, we had to raise the average removal rate even higher. We ran countless experiments and tests, but that final barrier held.

Crushed bumpers before paint removal. Multiple colors remain mixed in and recycling material in this state compromises material strength.

Usui:

How did you eventually break through?

Moriwaki:

We'd exhausted our options with Takase but continuing on our own would get us nowhere. We needed fresh partners.

It was then that my supervisor said something that changed our approach: "Don't limit yourself to automotive or recycling. Talk to people in other industries. They might have solutions we'd never consider."

That's when Satake came up. A rice milling equipment manufacturer in Hiroshima. They make machines that scrape hulls off brown rice. We wondered if that technology could work for paint removal.

Usui:

So you looked outside the industry. Rice milling technology for paint removal.

Moriwaki:

Right. I wasn't confident it would work. But at that point, I was grasping at straws. I went to Satake anyway.

Shifting Perspectives Until the Breakthrough

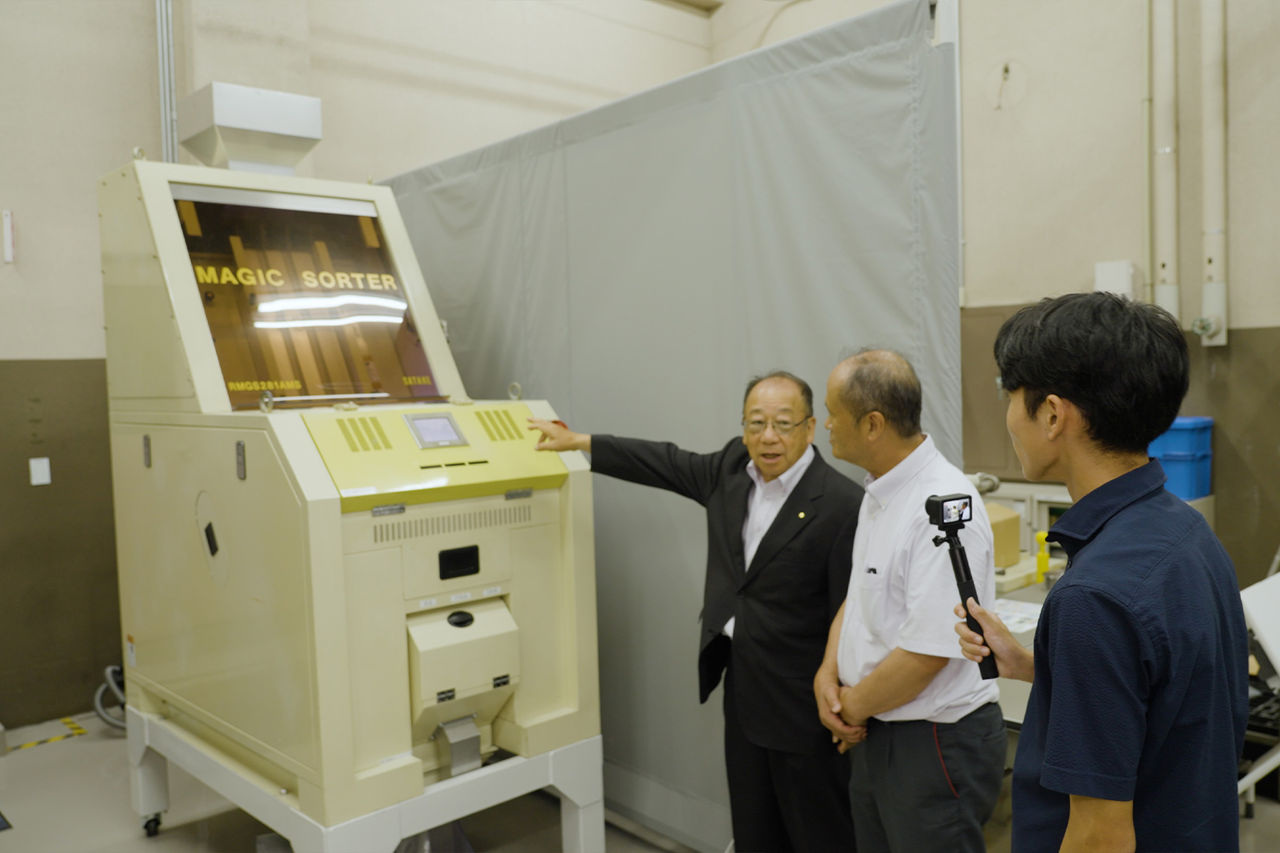

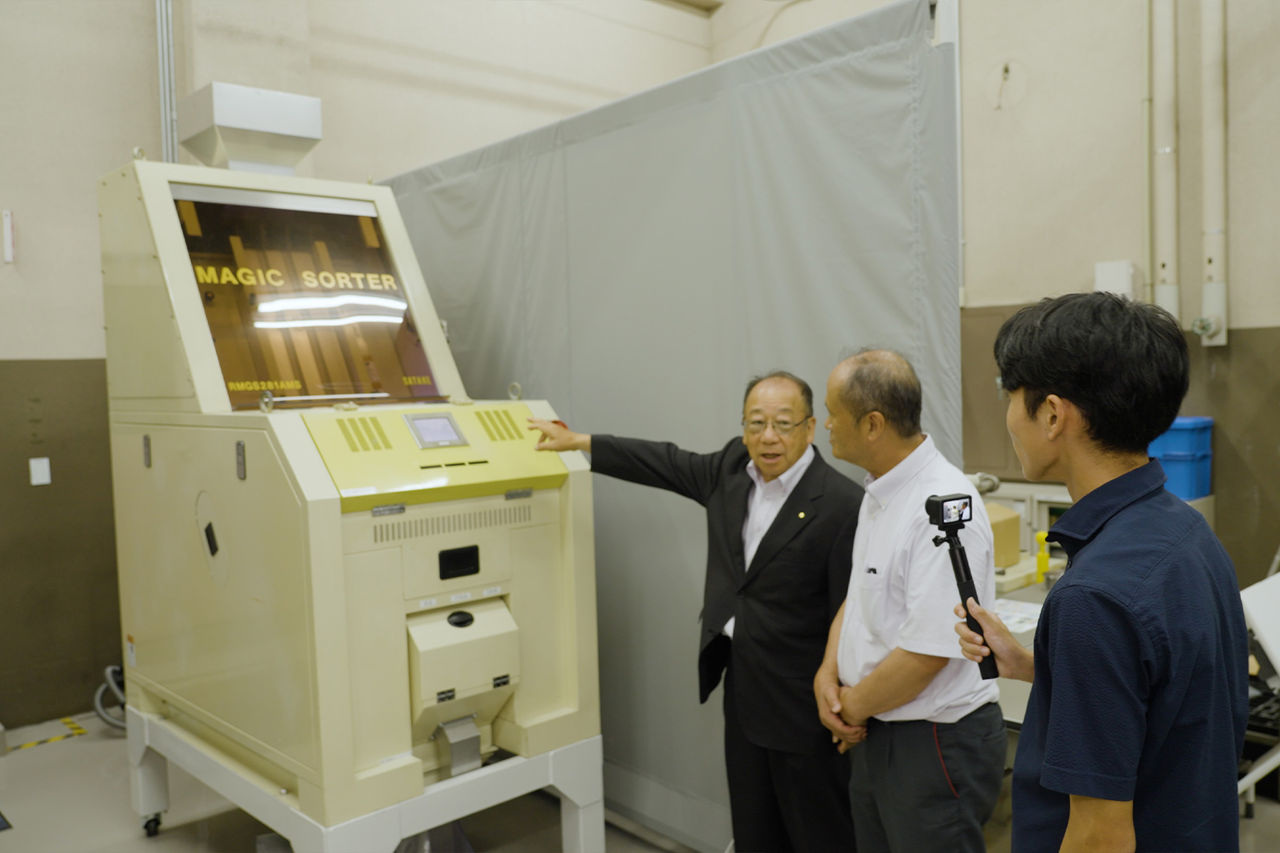

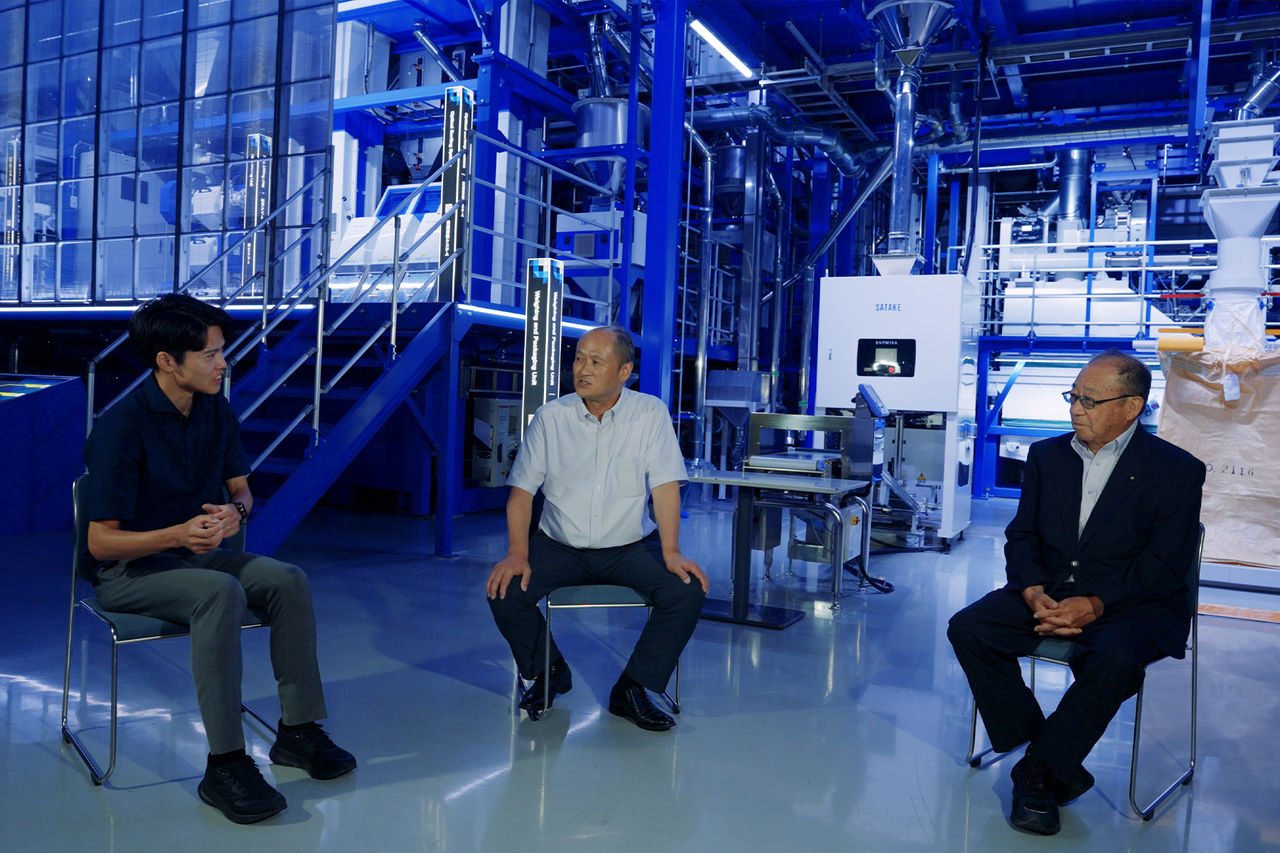

Moriwaki and Usui headed to Satake Corporation, the leading rice milling equipment manufacturer in Japan. After exhausting every improvement they could devise without reaching their goal, Moriwaki and his team sought help from outside the industry. They visited Satake's factory hoping for a breakthrough, where they made an unexpected discovery.

Usui:

Ito, you were part of the development team then. When Mazda first approached you asking whether rice milling technology could scrape off paint, what was your honest reaction?

Ito:

We'd actually processed materials other than rice before. Occasionally we received requests to peel corn husks or coffee bean skins using our equipment. So the request itself didn't surprise me that much, but a car manufacturer was certainly a first.

Takafumi Ito (right) of rice milling equipment manufacturer Satake Corporation.

Moriwaki:

But no matter how many times we ran the machine, we couldn't get it to work properly. We could remove some paint, but traces always remained. I was ready to give up and head home when Ito said, "Since you're here, would you like to see our other equipment?"

That's when I saw the optical sorter. Using a camera, it detects foreign objects mixed in with white rice, or spoiled grains that had turned black. Then it blasts them out with a jet of air. As Ito explained it, something clicked: what if instead of trying to scrape off the paint, we simply ejected the pieces that still had paint on them?

A rice optical sorter underwent internal modification to enable it to eject paint-covered material.

Usui:

So you made a complete shift in thinking. The original approach with the rice milling machine didn't work, but the solution was right there.

Moriwaki:

Exactly. We found our answer from an unexpected direction. It reinforced how important it is to look at problems from different angles.

We tested the optical sorter later and got promising results. From there, Satake, Takase Gosei Kagaku, and Mazda officially launched joint development.

Usui:

Did development proceed smoothly after that?

Ito:

Not at all. We hit a significant wall almost straightaway. Bumper paint comes in many colors, unlike rice grain. The optical sorter handles some colors better than others. Detecting various colored contaminants against a black base, which is typical for bumpers, proved especially difficult. We could sort to a degree, but complete removal seemed impossible. We struggled with it for quite some time.

Usui:

The concept was sound, but the existing technology couldn't handle it as-is.

Ito:

Right. Taking a conventional approach wasn't sufficient. We needed to rethink the problem. That's when I recalled my earlier work with coffee bean sorting. More than a decade before Mazda approached us, a specialty coffee shop asked us to remove beans with subtle color variations from roasted batches. We succeeded by adjusting the light wavelength. I wondered if we could apply that same principle here.

Standard sorters use visible light, wavelengths the human eye can detect. But by using a different, specific wavelength, I thought we might be able to make subtle paint colors stand out against the black base material.

It worked better than expected. After all that struggle, being able to give Moriwaki what he needed and meet his high standards felt really good.

Moriwaki:

Thanks to the combined efforts of Satake and Takase Gosei Kagaku, our paint removal rate improved dramatically. When we finally broke through that 98.5% barrier and hit our target, I nearly jumped for joy. This was an industry first, after all. We'd accomplished something no other car manufacturer had managed.

The optical sorter uses light wavelengths to distinguish and remove different colors.

The Bumper to Bumper process: Used bumpers collected from the market are recycled, crushed, reused, and transformed into new bumpers.

Inheriting Technology and Passion to Create a Better Future

Through Takase Gosei Kagaku's crushing and paint removal technology, combined with Satake's optical sorting capabilities and the persistent efforts of engineers, the team ultimately achieved high-purity recycled materials with a 99.9% paint removal rate.

The industry-pioneering Bumper to Bumper became reality. Since launching in 2005, approximately 1.27 million bumpers have been given new life. Beyond the technical achievement, the stable production that enabled recycling at scale earned recognition. In 2011, Bumper to Bumper received the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry's Industrial Science, Technology and Environment Policy Bureau Director-General's Award.

This is the origin of Mazda's recycling efforts, and that DNA runs through Mazda’s development teams today. Like Moriwaki and his colleagues, Mazda will keep working alongside regional partners, taking on challenges one by one. That’s how Mazda shapes the future of the car industry and creates a brighter future for our planet.

Usui:

Moriwaki, thank you for your time today. I had no idea there was so much struggle and experimentation behind Bumper to Bumper. And I was really moved to learn that this was accomplished by an all-Hiroshima team, right here in our home region.

Moriwaki:

Hiroshima is abundant with companies who have remarkable capabilities. Obstacles we can't overcome alone often have answers in other industries. Bumper to Bumper proved exactly that. Whatever challenges we face going forward, whether in recycling or other areas, we'll keep working with partners across industries and never stop pushing forward.

From the Editorial Team

The car industry faces significant challenges. I sense there's hesitation to pursue initiatives where success isn't guaranteed. That's precisely why seeking outside expertise and tackling difficult problems one step at a time, as a unified region, becomes the path forward. Those challenges create our future. Hearing firsthand from the people who overcame real obstacles and established world-first technology reinforced this conviction.

Just as cars continue evolving, recycling practices keep changing too. Knowing that new challenges are being addressed right now in the field, working to pass on limited resources to the next generation, my expectations for the future have grown, not just as an employee but as a member of society.

Movie